ON THE HISTORY OF PLACE NAMES

My previous posts (part 1 and 2) have been concerned with a

castle ruin called Karlsborg, to the south of Hamburgsund. I have tried to put

this rather unexplored ruin into a historical and economic context. More

questions have been raised than answered by my investigations, and it is

necessary to further explore this castle using both microscopic and macroscopic

forms of research. Today, we will be investigating the historic place names of

Bohuslän in general, in order to see what this information might tell us about

the context of Karlsborg.

The use of place names in historical

research is, according to me, somewhat controversial, at least in more

deterministic forms of toponomy. We need to exercise caution when using this

information as a base for our interpretations, as it is sometimes difficult to

know exactly when a place was

named, and why. However, toponomy in

Sweden is based on profound research, both linguistic and historical, and it is

an intriguing material to use.

Beneath, I have selected some general

elements in place names, from different periods, and tried to analyse their

geographical patterns through the use of GIS. As I am quite the novice in the

use of place names in historical research, I ask you not to take this

analysis too seriously. The material used is heavily generalized, and a closer

investigation would be needed in order to use this in more serious research.

However, I think that even this shallow analysis have provided me with a nice

picture of the historical development of Bohuslän’s settlement patterns.

Prehistoric Place Names

A map showing prehistoric place names in Bohuslän. The white line marks the border of Bohuslän to neighboring counties.

Blue: -by

Blue: -by

Purple: -hem

Light green: -landa

According

to traditional toponomy, there are certain place names that can be traced back

to a pre-christian period. In Bohuslän, these are names ending with either “-by”,

“-hem” or “-landa”, e.g. “Svenneby”, “Solhem” or “Kavlanda”. The map shown above is made by

selecting present day communities with these elements present in their names. It

is clear that “-by” is the most common prehistoric element in Bohuslän’s place

names. We should also note, as seen in the map above, that inland Bohuslän is

quite devoid of communities with prehistoric place names. This might illustrate

that settlements, at least in the late iron age, were

shaped by the fact that most arable soils in this region are located close to

the coast. We can also assume that these rural communities, though mainly

agricultural, also considered fish an important part of their sustenance.

Medieval Place Names

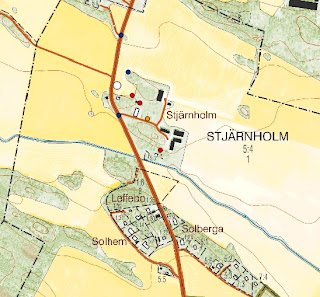

Map showing settlement development in the middle ages. The white line marks the border of Bohuslän to neighboring counties.

Blue: Prehistoric names

Purple: -hult

Orange: -rud

Brown: -röd

Pink: -torp

Place names from the medieval period in

Bohuslän usually contain the elements “-röd”, “-rud”, “-torp” and “-hult”. Most

of the medieval names in Bohuslän contain the element “-röd”, referring to

cleared ground, and often cultivation. The map above shows a potential

development from prehistoric to medieval times, were most of the densely

forested area have been colonized. Usually, this phenomenon have been connected

to the population growth of the High Middle Ages which, along with

technological development, allowed previously quite uninhabited areas to be

settled. The initial expansion was halted in the middle of the 14th

century, with the outbreak of the Black Death and the following economical

decline, also in combination with the environmental change to what have been

called “The Little Ice Age”.

The redoubled amount of settlements seen in

the map should not be interpreted as a redoubling of the population during the

High Middle Ages. Most of these new settlements were small, lacking the more

extensive farmlands found in older communities. Perhaps, we can connect this

new settlement pattern to an increased use of the forest itself, but this

requires further investigation. Timber was important trade goods in medieval

Scandinavia, but whether the settlement expansion in Bohuslän is connected to

this, we cannot at the moment tell.

Karlsborg and Place Names

Place names around Karlsborg

Blue: Prehistoric names

Brown: -röd

Pink: -torp

This

investigation has not clearly shown any connection to the region around

Karlsborg. We cannot observe any community name in the immediate area

containing the historic elements under study. The closest settlements are

Svenneby, Smedseröd, Skogby and Allestorp, all presumably existing

simultaneously with the castle and within a 8km radius.. However, they do not

indicate any certain importance connected to the location of Karlsborg. This

might be explained by the fact that we have excluded many historic places in

our investigation (important places such as Dynge, Apelsäter, Hallinden and

Vettland are not included), where we have sought a general pattern rather than

interesting particularities. More local place names, among them the names of

rivers and natural features, should be taken into account when conducting a

more localized analysis.

If we ignore the above criticism, however

vital it may seem, we can assume that the region was not particularly important

or special in the High Middle Ages, and that the importance can be connected to

the later middle ages. Many of the place names in the investigation above

defines settlements founded in the initial expansion of the earlier middle

ages, and the pattern may have

changed during the later middle ages. If the area around Karlsborg had been

previously unimportant, it would explain why the site was not extensively

fortified until the middle of the 15th century. This, at least in a

very generalized way, supports the idea of seasonal fishing, caused by a

herring period, as a foundation for the importance of Hamburgsund and

Karlsborg. While written history does not support this theory, it is not

unlikely. Maybe be the lack of documentation of this period can be traced to a

high degree of international activity in the area. More on this in coming

posts!

That was

all for now! As usual, you are more than welcome to share your thoughts and

ideas on the topic discussed. If you found this post interesting, feel free to

leave a comment!